| Home Page

About Page

Jordan

Jokes

funny pic

Kiko

Things i love

Favorite Links Page

Flowers1

Flowers2

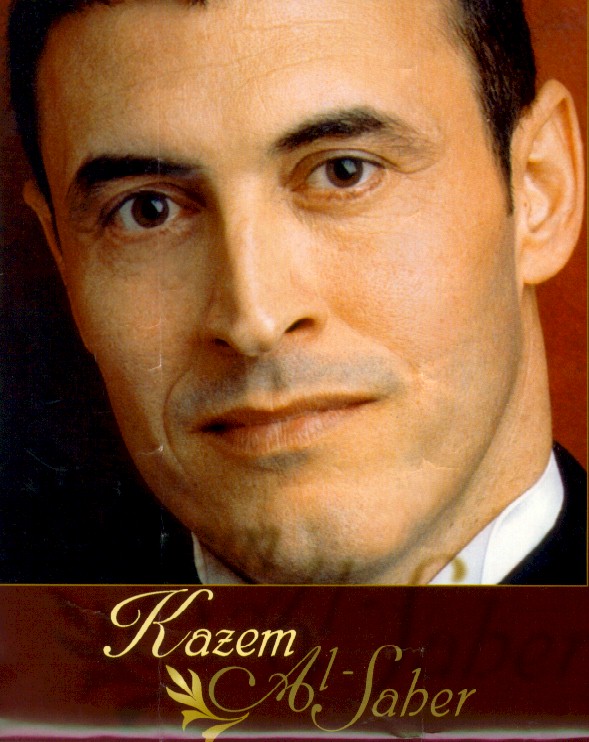

Kathem El Saher

Cars..Mercedes

Contact Page

Now in Cinemas

Great Words

Ohhhhh Laaa Laaaaa

Guest Book

Slide Show Page

|

|

|

ABOUT ..

Kathem was born in Samuraa (Iraq) where he lived a very modest childhood in a familly composed of 10 children. He loved the music so much that at the age of 15 and contrarly to the children of his age, he sold his bicycle to buy a "Oud" a very famous Arabic Music Instrument. After completing his High School, Kathem joined the Higher Instute of Arabic Music in Baghdad where he learned to play the Oud from the very famous Iraqi Oud Player Mounir Basheer. He adored the music of Mohamed Abdel Wahab, and the poems of Nizar Qabani and composed while he was still studying, the music of "Iny Khairtouky Fakhtary" a very famous poem for Nizar Qabani.

In the begining of the 80's, Kazsem started his career and become one of the best to sing Love and the Iraqi Folklore and a made an excellent success with his song " Abart El Shat ".

Following the Gulf War in 1990, Kathem moved to Lebanon where he become in a very short period of time a very well known singer and a super star in the Arab world. All his songs music are written by himself while the words are written either by Kareem Al Iraqi or are poems of Nizar Qabani.

Kathem was made many tours and concerts around the world ,

mainly in the Arab world, Europe , the U.S and won the Unicef Award for his song "Tazakar". His songs such as " "Zeediny Ishkan" , "Ishhadou Ana La Mraatan Ila Anty " and "Alamany Hobouky" made an excellent hit in the Arab world and are till today one of most requested songs of Kathem.

Kathem composed music for Lateefa and Majida Al Roumy and is preparing now for a big Symphonie which will be played in Rome Italie for Christmas 1999 along with a group of the biggest and famous Italian and European singers.

|

| |

Kathem Saher

Wherever he performs, he agitates a legendary revolution. He has occupied a high rank among the Arab singers, he is known as the First Arab Star or the 'Enchanting Artist.'

Kathem Saher's love for music appeared since he was a young child when he used to repeat the songs of Abdulhalim Hafez and Abdul Wahab. He started at twelve years old when he sold his bicycle to buy a ‘Oud,’ which stopped him from playing with children and started him on playing instruments.

Besides his love for poetry and music he lived on Nathem Al Gazali’s voice.

He studied at the Teachers School, and joined the Salwa Ahamilian Group, who taught him singing for two years at the Fine Arts Center. In 1981, he joined the National Music Center in Baghdad where his teacher was the Oud Professor Munir Bashir. At the Baghdad Center he studied Eastern singing and Oud playing and recorded several songs. It was when the singer reached his twenties that he started composing and performing his own work.

It was not until 1987 that the singer became a star in his hometown of Baghdad.

In the early nineties, his first concert in Amman increased his popularity and so did his concert in Lebanon, in 1992.

Esteemed poet Nizar Kabani discovered Saher. Till now he proudly says: "Nizar wrote 'Zidini Ishkan' for me and still I feel fear whenever I want to compose his poems."

Saher's most favorite song is 'La Ya Sadiki,' which consists of 85 lines of the best poems written for love and friendship.

Besides his cooperation with the late Nizar he also likes working with writer Abdul Wahab Mohammed.

After years of successful performances held in Lebanon, Jordan, Tunis and Egypt, Kathem gained the Crown of Arabic Singing in the Arab region and the world consecutively. If he is ever asked about the secret of his success, he would reply; “I do not have any reason, but for me it is the respect of the audience.”

|

Kathem

Kathem |

| |

Edit a custom page for your Web site:

This is the ideal place to design your own custom page, filled with whatever you can imagine from products, pictures, fan clubs, links or just more information. |

Looking 4 you

Looking 4 you |

| |

Edit a custom page for your Web site:

At the age of 10 he learned the guitar and by 12 he was writing qasidas (verses) that his peers couldn't believe a child had composed. He entered Baghdad's prestigious Music Academy, and after graduating began a career as a songwriter for already established singers in Iraq. But his reputation as a singer and songwriter in his own right began to spread. In Lebanon and the Gulf, his renditions of folksongs of south Iraq won an admiring audience.

Yet life in Iraq was getting increasingly difficult. During the Iran-Iraq war he spent more and more time out of the country. The 1991 Gulf war marked the end; he moved his family to Canada and spent nearly all his time singing to Arab audiences abroad. With no particular effort on his part, he found himself cast as a singer in exile, though he was returning to Iraq on average once a year. His love songs, his fans would presume, were thinly-veiled paeans to his long-suffering homeland. For him, too, that's what they eventually became.

Then in 1994 an Egyptian television chief chanced upon some recordings. He was astounded. "This boy's a genius," he reportedly said. So Saher was ferried in from Tunisia, where he had been an instant hit, to perform on Channel One's "Television Nights." He was introduced as "an Arab singer." A year later, and after a thaw in political relations between Egypt and Iraq, he was "the Iraqi star." Now he is probably the most popular, and certainly the most critically-acclaimed, singer in the Arab world. And he has done more than anyone else to bring the tragedy of Iraq home to the Arab masses.

His appearance confounds expectations. In concert and on album covers, he is always immaculately turned out in a suit, a tie, and without a hair out of place. But now Kazem Al Saher is wearing a baseball cap and a white sweatshirt. He's also a lot shorter than television implies. Still, his face gives off the same angelic look of utter integrity that had women swooning over Abdel Halim Hafez a generation ago. He's dressed young, but he's here to rave about the past.

His new album Ana wa Laila (Me and Laila) is, as he puts it, a return to tradition, classicism and romance. This is the Laila of the classic tale of tragic love, Qays and Laila, the Arab version of Romeo and Juliet. Since the Cairo music industry marketed Saher as a superstar all over the Arab world -- this is his fourth Cairo-based album in three years -- his music has been notably retrogressive in its references and tone. Words matter in the Arabic song, and Saher is one of the few stars of sufficient magnitude for Nizar Qabbani, one of the giants of modern Arabic poetry, to pen verses for him. Saher has even put to music a romantic poem penned by Qabbani 30 years ago Zidini Ushqan (Increase My Passion), making it relevant to contemporary audiences.

When he came to Cairo, producers told him he was crazy. He shunned synthesizers and insisted on bringing players into the studio to do the tiniest bit-part for a flute or piccolo, and he travels the world with a full 35-man band. In a world full of shaabi music moans and Amr Diab chic, Saher is unashamedly classical, a modern star clearly placing himself within the firmament of tradition, yet still managing to appeal to young people. "He came with a new trend of singing, which we haven't seen for at least 15 years," says Iraqi journalist and friend Lena Mazloum. "Arabic pop music has seen new technology applied in a haphazard way, and a million companies and singers have appeared. Amidst all this, Kazem came with a form of singing, a bit classical, but new for our generation -- romantic, imaginary love."

It's not just his voice, it's his choice of maqam -- a scale or chord -- and the way he moves from one to another, experts say. "I do it in an unconventional way, because the thing is there aren't actually any rules about how you should move between them," Saher says. Musicians say that more specifically what he has done is to revive maqams that died with composer Mohammed Abdel Wahhab as well as bring to the rest of the Arab world uniquely Iraqi musical structures -- some of which date back to the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad -- which had become lost in the cacophony of modern Arabic pop. "He's a great singer," says renowned nay (flute) player Qadry Sorour, "but he also sings with an awareness of the roots of Arabic music. As with others in Iraq, he has been trained in an authentic sound."

Coupled with his good looks and a well-honed sense for the pop ditty, Saher has managed to make this authenticity sell. "There's a desire amongst the music-listening public for the classical sound," he says. "And this is my way of doing things, I like to go back to the classical sound, with a full orchestra -- I always have. I don't like my sound to be too easy, I want it to be difficult, and the words, too." At the same time he tries to deal with "humanitarian issues," as he says -- such as in the song Ya Sakina, about a Christian and a Muslim from the same quarter falling in love.

Then there are the songs about his country. Forces seem to have conspired to have cast him as the human face of Iraq. The song that first bowled over his Egyptian audience -- Salamtak Imn Al Ah (Keep Safe from the Pain) -- has entered popular imagination as a lament to his troubled country. He says it was simply about someone very dear to him. "But once I was performing it at Carthage [song festival in Tunisia] and while I was on stage, I began thinking of Iraq and told the audience. In Iraq they began to say it was about them," he says. At a concert in Dubai earlier this year, he sang Tadhakkar (Remember) about children dying on the streets of Baghdad. It hasn't appeared on any album, but news of the song spread via the huge Arabic entertainment press. And Mickey Mouse music companies have pirated concerts he's done in America and sold them on an album they entitled Exile.

Even political commentators have noted the sympathy for Iraq's plight he has evoked from Arab audiences, even in Kuwait where he has performed. "He has become famous because of the suffering of Iraq," says political writer, Nabil Abdel Fattah. Samir Ragab, editor- in-chief of Al Gomhoriya even accused him of being an agent for Baghdad. Iraq's ambassador to the Arab League Nabil Negm, Ragab noted, is "always seen at his concerts." Saher doesn't even appear to have known about the accusation. "Really? I can't believe he said that. Who is he?" he asks in disbelief. He's even been the subject of an alleged assassination attempt in Jordan. "There are a lot of robbers on the road between Amman and Baghdad and once I got out to help some people who'd been attacked. But people started saying it was me who had been attacked," he says. Says arts critic Essam Zakaria: "People thought the Iraqi opposition perhaps tried to kill him because he has become such a good face for Iraq." And yet, he is as much negative as positive propaganda for the regime -- he is the singer of the exiles after all. "He is a bearer of the pain of Iraq, rather than good propaganda. Iraq is a very fragmented society, and he has managed to unite them," says Abdel Fattah. "He has become a national symbol." In this he follows in the tradition of exile singer of the 1950s and 60s Nazem Al Ghazali.

Saher's relations with the regime is a more personal and serious issue than this suggests, though. People close to him say he has to walk a thin line between paying his respects to Baghdad and keeping his distance. The arms of the regime are long, and he has to make an appearance at major events on the political calendar like presidential birthdays. Most of his family remains in Baghdad after all. They've been subject to threats before, associates say. "He can't cut his links," says Lena Mazloum. "Any Iraqi abroad nowadays is obliged to be on good terms with the regime."

After leaving one's country, anyone with a heart couldn't avoid wanting to sing of the grief of his country's fate, especially when it's as bad as Iraq's. This year Saher performed in London's Royal Albert Hall for charity. Colleagues say he devotes a part of his income to the poor of Iraq, though he keeps that away from the Arabic media. "Inside Iraq there's a lot of sadness, and it really affects you -- the sight of the people and the children, it's a tragedy. I try not to forget my country when I move around, but I also try to find a balance of sad songs and happy songs," he says. "I don't want to get into politics, but I don't want to forget the children and my country. Who's wrong and who's right, I don't know." Now that he's in Cairo, he feels more at ease. "I didn't have a country before, I was just going from one airport to another. We were living in Canada officially, but now I have Cairo, mainly because there are studios here and that's where I live, really."

Saher prefers to see his popularity as a form of cultural rather than political propaganda. He says he is filling in a cultural void in the Arab world brought about by Iraq's isolation. When Egypt opened itself to Saher, it went some way to rectifying that isolation. An Iraqi music ensemble was in Cairo earlier this year, and celebrated oud player Nosseir Shama is due to perform here during Ramadan. "People have started to appreciate the Iraqi dialect," he says. "Some countries didn't really know a thing about Iraq before. But we've opened their eyes and made people realize that we are here." He's restoring a balance, he says. And yet the harsh truth is that if Egypt- Iraqi relations are to take another sudden nose-dive there's little doubting Saher will be off the TV screens.

There are other dangers lurking, too. Jealousy abounds in the music industry, and there has been no end of Saher stories in the press -- usually suggesting that he thinks Egyptian musicians aren't up to standard. He was briefly blacklisted last year by the Musicians Syndicate after he was quoted in a Tunisian paper bemoaning players in Cairo. Luvvies have also sniped that he isn't the best in Iraq in any case. Iraqis say though that there may well be better voices, but none have his charisma. Colleagues have warned him to be careful. A talented singer who writes much of his own material and pens a good deal of the lyrics isn't so much a potential victim of the evil eye as in danger of losing himself in his own artistic indulgences. In short, he needs to diversify if he isn't to fall victim to his own success. "A one-man show is a very dangerous game to play," says Lena Mazloum. Also, he tends to choose his collaborators badly. He penned an album for lesser light Latifa, but it flopped because she just didn't have the voice to pull it off. Now he's planning a film -- though he won't say what about -- and is to get together for an album with Lebanese star of similar stature Magda Roumi.

Saher cuts a haunting, almost vulnerable profile. A striking talent with a heart of gold living in uneasy exile from a country in crisis. It's a story with all the makings of the romance and tragedy of one of his songs.

|

....

.... |

|

|